Read an extract from Jane Austen in 41 Objects

Read an extract from Jane Austen in 41 Objects

In this extract from Jane Austen in 41 Objects, Kathryn Sutherland explores a teenage notebook, one of the earliest examples of Jane Austen’s work, as an antidote to the ‘Janeite cosiness’ of this writer in the popular imagination.

‘4. Volume the First’

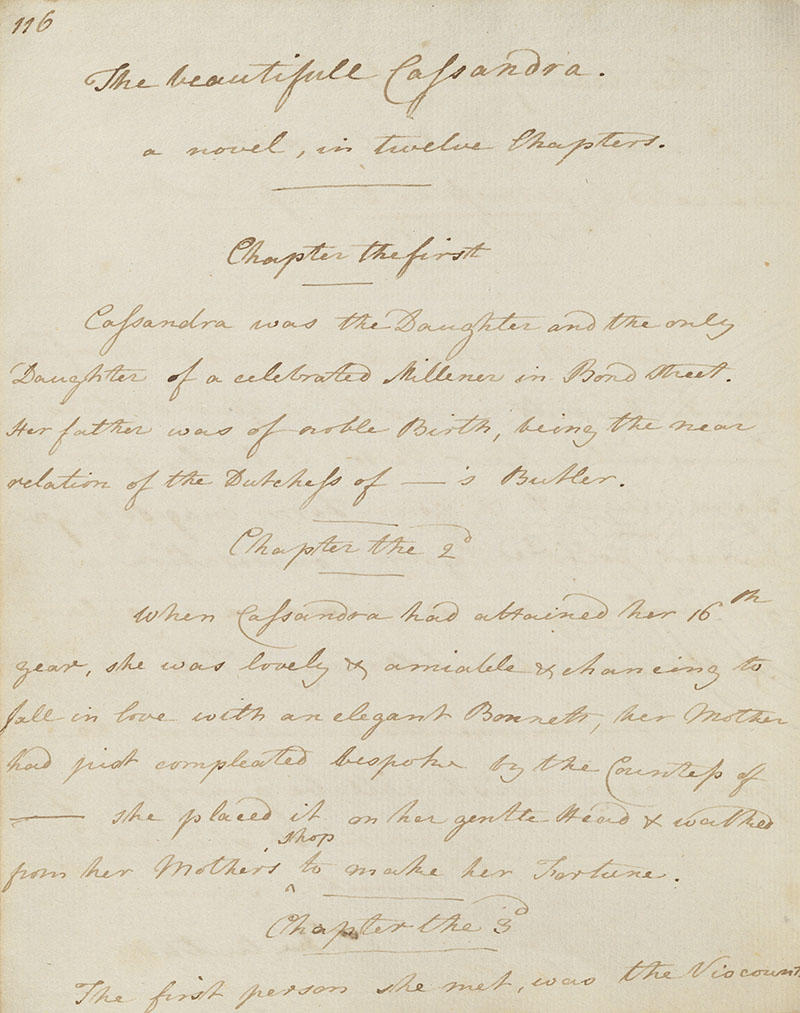

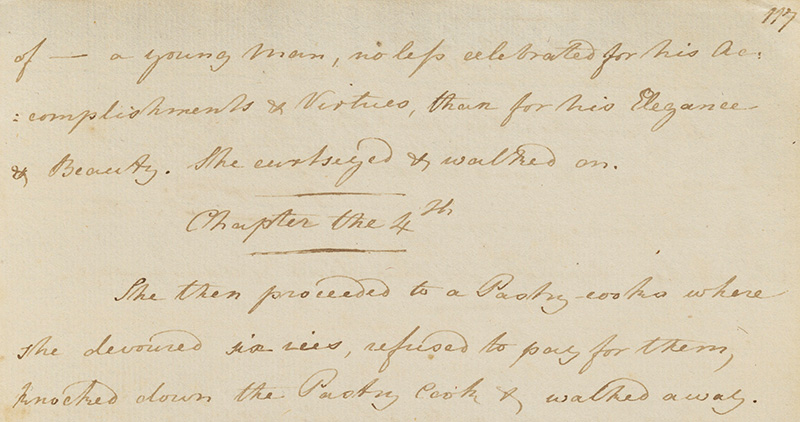

Jane Austen's favourite word, aged twelve, was ‘author’; no false ladylike modesty here. Affixed thirteen times to the overblown dedications of her capsule teenage stories by this not so ‘Humble Servant’, the word also intrudes, perhaps unawares, into the misspelled name of ‘Sir Author’ (corrected to ‘Sir Arthur’) in her playlet ‘The Visit’. She made fair copies of sixteen short works, composed from age eleven or twelve to seventeen, in this notebook—stories, play sketches, verses and moral fragments. The final entry is dated ‘June 3d 1793’. They represent some of the earliest surviving examples of her hand and art.

Written to show how clever she knew she was, these spoof tales poke fun at the limited syllabus passing for female education among well-bred families at the close of the eighteenth century. In them, she introduces young girls whose tastes run less to needlework, home economics and history lessons than to boys, gambling and strong drink. At a time when teen fiction (like the recognition of adolescence as a cultural and psychological state) scarcely existed, the young Austen used wilful misreading to test the limits of both writing and female conduct.

Her teenage characters live out appropriate teenage fantasies: they disown their parents, run away to seek their fortunes and invent new identities; they become orphaned only to discover wealthy and noble relatives. Characters in flight, their adventures lie somewhere between folk tale, fairy tale and cartoon, with their familiar mix of economy and extraordinariness. Their stories are prone to disgression and sudden shifts in topic—devices for postponing or altogether abandoning the ending, and for avoiding consequence.

Nothing proceeds as you would expect in a novel by Jane Austen. Brief sketches, they leave something unresolved. For heroines like the foundling Eliza Harcourt Cecil and the ‘beautifull’ Cassandra, the future is unprescribed, open to new possibilities. Stealing from her foster parents and eloping with her friend’s lover, Eliza squanders a fortune, survives prison, and raises an army to destroy her enemy, the mother of the friend she betrayed. The fake aristocrat Cassandra, daughter of a Bond Street milliner and the ‘near relation’ of a duchess’s butler, falls in love with an elegant bonnet and rampages around London accosting and stealing from tradespeople.1 Rebel girls, their lives spool on, frame after hectic frame, in the present continuous time of cartoon reality. No bad action goes unrewarded.

Years later, a published novelist, she shared her early notebooks with her teenage nieces and nephew in creative writing classes held at Chawton Cottage. Looking back, the writer of far different novels about circumscribed female futures, did she feel something of the longing soon to be expressed in Catherine Earnshaw’s cry: ‘I wish I were a girl again, half-savage and hardy, and free’?2

Austen's teenage voice was not heard outside the family for more than a hundred years, its members fearing exposure to public scrutiny of Aunt Jane’s youthful writings. To Virginia Woolf, reading them for the first time in 1922, their content and style proved a revelation, an antidote to a popular reputation so comfortable it was oppressive.3 After another hundred years, the antidote against Janeite cosiness that Eliza, Cassandra and their bolshie sisters administer is just as necessary. The good news is that it is just as effective.

Bound in quarter-tanned sheepskin over boards sided with common late-eighteenth-century spot-marbled paper, this quarto notebook takes its name, ‘Volume the First’, from the calligraphic inscription on its upper cover. Passed down in the family of Austen's youngest brother, Charles, it was bought by the Friends of the Bodleian, Oxford, in 1932 for £75, considered at the time a remarkable bargain: the manuscript of another early Austen work, Lady Susan, selling only months later at Sotheby’s, London, for £2100.

Kathryn Sutherland is Senior Research Fellow at St Anne’s College, Oxford.

1 See 'Henry and Eliza' and 'The beautifull Cassandra', in Teenage Writings, ed. Kathryn Sutherland and Freya Johnston, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2017, pp. 27-32, 37-40. (return)

2 Emily Bronte, Wuthering Heights, 1847, ch.12 (return)

3 Virginia Woolf, 'Jane Austen Practising', New Statesman, 15 July 1922, her review of Love & Freindship and Other Early Works, now first printed from the original ms. by Jane Austen, preface by G.K. Chesterton, Chatto & Windus, London, 1922. (return)

Jane Austen in 41 Objects

Kathryn Sutherland

Bodleian Library Publishing

Hardback

226 pages

70 colour illustrations

£25.00